Capacity

What impaired capacity means

The law presumes that every adult has capacity to make their own decisions. You can’t assume someone has impaired capacity without clear evidence.In Queensland, ‘Capacity’ is defined as a person’s ability to

- Understand the nature and effect of decisions

- Freely and voluntarily make decisions

- Communicate those decisions in some way.

The law states that people with impaired capacity have a right to adequate and appropriate support in decision-making. Also, they may be able to make some types of decisions but not others. Capacity needs to be considered in the context of the decision to be made.

Reference: Qld Govt – Making Decisions For Others

Capacity and Informed Consent for Treatment

Before treatment can be administered to a person, a clinician must seek the informed consent of the person.Capacity is the ability of that person to give informed consent to a particular treatment at a particular time.

The clinician must presume that the patient has capacity to give informed consent to treatment.

This presumption of capacity can be rebutted if it can be shown that the patient does not have capacity to give informed consent at the time a particular treatment decision needs to be made.

Assessment of capacity is a complex matter.

The Act outlines the many different aspects of the person’s understanding and appreciation of their illness and treatment that encompasses a full assessment of capacity.

All of these elements must be addressed in a capacity assessment.

Clinicians must be aware that capacity is specific to the decision that needs to be made at the time (i.e. a person’s capacity to consent to treatment is distinct from the person’s capacity in relation to managing finances or driving a motor vehicle).

Additionally, a person might have the capacity to consent to some aspects of treatment and care but not to others.

Clinicians must provide patients with all of the relevant information in making treatment decisions, and must support persons in making all treatment decisions - with the use of interpreters, visual aids, simple language or any other means necessary.

Clinicians must ensure the patient has been given a reasonable period of time to consider matters involved in the decision, reasonable opportunity to discuss the decision with the health practitioner, opportunity to seek advice, support and assistance, adequate information on the treatment, alternatives, advantages, disadvantages and beneficial alternative treatments.

Clinicians must be aware that a person’s capacity to make treatment decisions can fluctuate over time. Reference: CP Policy Treatment Criteria and Assessment of Capacity

Assessing Capacity

Assessing Adult Capacity for Decision Making Guide and Toolkit (Dept Health)Who Can Decide? The Six Step Capacity Assessment Process

- Ensure a valid trigger is present.

- Engage those being assessed.

- Information gathering.

- Education.

- Capacity Assessment.

- Act on results.

A capable person:

- knows the Context of the decision at hand (is not making choices based on delusional constructs)

- knows the Choices available

- appreciates the Consequences of specific choices

- applies logical reasoning to Compare between choices

- is Consistent in their choice (no undue influence)

- is able to Communicate their choice

Triggers for Capacity Assessment

When should capacity be Assessed or Reassessed?

It is not always obvious when a person can’t make a specific decision. However, particular circumstances, events or behaviours might lead you to question a person’s capacity at a point in time. These are called triggers.Once you have judged that a trigger exists, a capacity assessment is the next step if all other attempts to solve the problem have failed and the conduct of the person is causing, or is likely to cause, significant harm to the person or someone else. Or if there are important legal consequences of the decision.

A trigger(s) alone are not yet evident of impaired capacity

Triggers that Involve Conduct

Triggers that involve the person’s conduct might include any of the following:- repeatedly making decisions that put the person at significant risk of harm or mistreatment

- making a decision that is obviously out of character and that may cause harm or mistreatment

- often being confused about things that were easily understood in the past

- often being confused about times or places

- having noticeable problems with memory, especially recent events, and which have an effect on the person’s ability to carry out everyday tasks

- dramatically losing language and social skills. For example, having difficulty finding a word, not making sense when speaking, not understanding others when they speak, having wandering thought patterns, interrupting or ignoring a person when they are speaking, or failing to respond to communication

- having difficulty expressing emotions appropriately, such as inappropriate anger, sexual expression, humour or tears without actual sadness

- displaying sudden changes in personality. For example, excessive irritability, anxiety, mood swings, aggression, overreaction, impulsiveness, depression, paranoia or the onset of repetitive behaviours

- declining reading and writing skills

- having difficulty judging distance or direction, for example when driving a car. Triggers that involve the person’s circumstances might include:

- not looking after themself or their home the way they usually do and this being bad for their health or putting them at significant risk. For example, neglecting significant personal concerns such as health, hygiene, personal appearance, housing needs or nutritional needs

- not paying bills or attending to other financial matters, such as running their business, repaying loans or other debts making unnecessary and excessive purchases or giving their money away, and this being out of character

- noticeably being taken advantage of by others, such as being persuaded into giving away large assets that they still require such as a house, car or savings, or signing contracts that disadvantage them

- having been diagnosed with a condition that may affect their capacity

- having lacked capacity to make decisions in the past.

NOTE: See also, the Qld Attorney General Capacity Assessment Guidelines (Due out March 2020)

Increased capacity

Another important trigger for assessment (or re-assessment) is when a person’s capacity improves. The person may simply have regained capacity lost through ill health or other circumstances. They may have learnt skills or accessed support services to increase their capacity. A person who could not make their own decisions in the past may now be able to do so if another assessment is conducted.Mental illness and fluctuation of capacity

If you are dealing with a person whose capacity fluctuates because of a mental illness, it is crucial to make an assessment when there is an indication of increased ability to make decisions. This will enable the person to have control over as many of their decisions as possible.Doubts About Capacity

What there are still doubts about capacity?

If there are still doubts about a person’s capacity after an assessment, you (or another individual) may want to get a second opinion about the person’s capacity from a general practitioner, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a geriatrician or a neuro-psychologist, for example. These second opinions could be used, for instance, by a:- legal practitioner to decide whether a person has the capacity to make a will or enter into a contract

- general practitioner to determine whether the patient can understand the nature and effect of a proposed treatment, or if a substitute decision-maker should make the decision

- healthcare worker to help decide whether a person has the capacity to make a decision about their accommodation arrangements

Should I seek a second opinion?

In some situations, a second opinion may be the only way to ensure a fair assessment of a person’s capacity. Factors that may indicate that a second opinion might be necessary are:- a dispute by the person concerned, who believes they still have capacity

- a disagreement between family members, carers, community workers or other professionals about the person’s capacity.

Remember, although getting a second opinion will help, the final decision about capacity is ultimately to be made by whomever it is that needs to know whether the person is capable of making the specific decision. That might be the individual who will be making the decision on behalf of the person (substitute decision-maker), or a community worker or other professional providing a service to the individual. More specific examples are a:

- family member needing to use a power of attorney

- lawyer writing an advance care directive

- bank manager approving a loan

- doctor assessing capacity to consent to medical treatment

- lawyer witnessing a document

Where a second opinion is unable to be obtained for reasons such as a dispute, urgency, location or lack of finances, the individual disputing the original capacity assessment may need to go to the Tribunal for a decision about a substitute decision-maker.

Reference: NSW Dept Communities and Justice Capacity Toolkit

Other International Perspectives on Capacity

United Kingdom

Assessing capacity If you think that an individual lacks capacity, you need to be able to demonstrate it. You should be able to show that it is more likely than not – ie, a balance of probability – that the person lacks the capacity to make a specific decision when they need to. An assessment that a person lacks capacity to make decisions should never be based simply on the person’s age, appearance, assumptions about their condition (includes physical disabilities, learning difficulties and temporary conditions (eg, drunkenness or unconsciousness), or any aspect of their behaviour. It is important to document any decisions you make in assessing capacity, and any reasons for the clinical judgement that you come to.You will need to assess a person’s capacity regularly, particularly when a care plan is being developed or reviewed. Other points Capacity is dynamic and a specific function in relation to the decision to be taken. This will need to be regularly assessed in relation to each decision taken, and carefully documented.

For more information visit: Medical Protection – An Essential Guide to Consent – Capacity

Effective assessments are thorough, proportionate to the complexity, importance and urgency of the decision, and performed in the context of a trusting and collaborative relationship.

Health and social care organisations should monitor and audit the quality of mental capacity assessments, taking into account the degree to which they are collaborative, person centred, thorough and aligned with the legislation.

Include people's views and experiences in data collected for monitoring an organisation's mental capacity assessment activity.

Organisations should ensure that assessors can seek advice from people with specialist condition-specific knowledge to help them assess whether, on the balance of probabilities, there is evidence that the person lacks capacity – for example clinical psychologists and speech and language therapists.

Organisations with responsibility for care and support plans should record whether a person has capacity to consent to any aspect of the care and support plan.

Organisations should have clear policies or guidance on how to resolve disputes about the outcome of the capacity assessment, including how to inform the person and others affected by the outcome of the assessment.

For more information visit: NICE Guidance Recommendations – Assessment of Mental Capacity

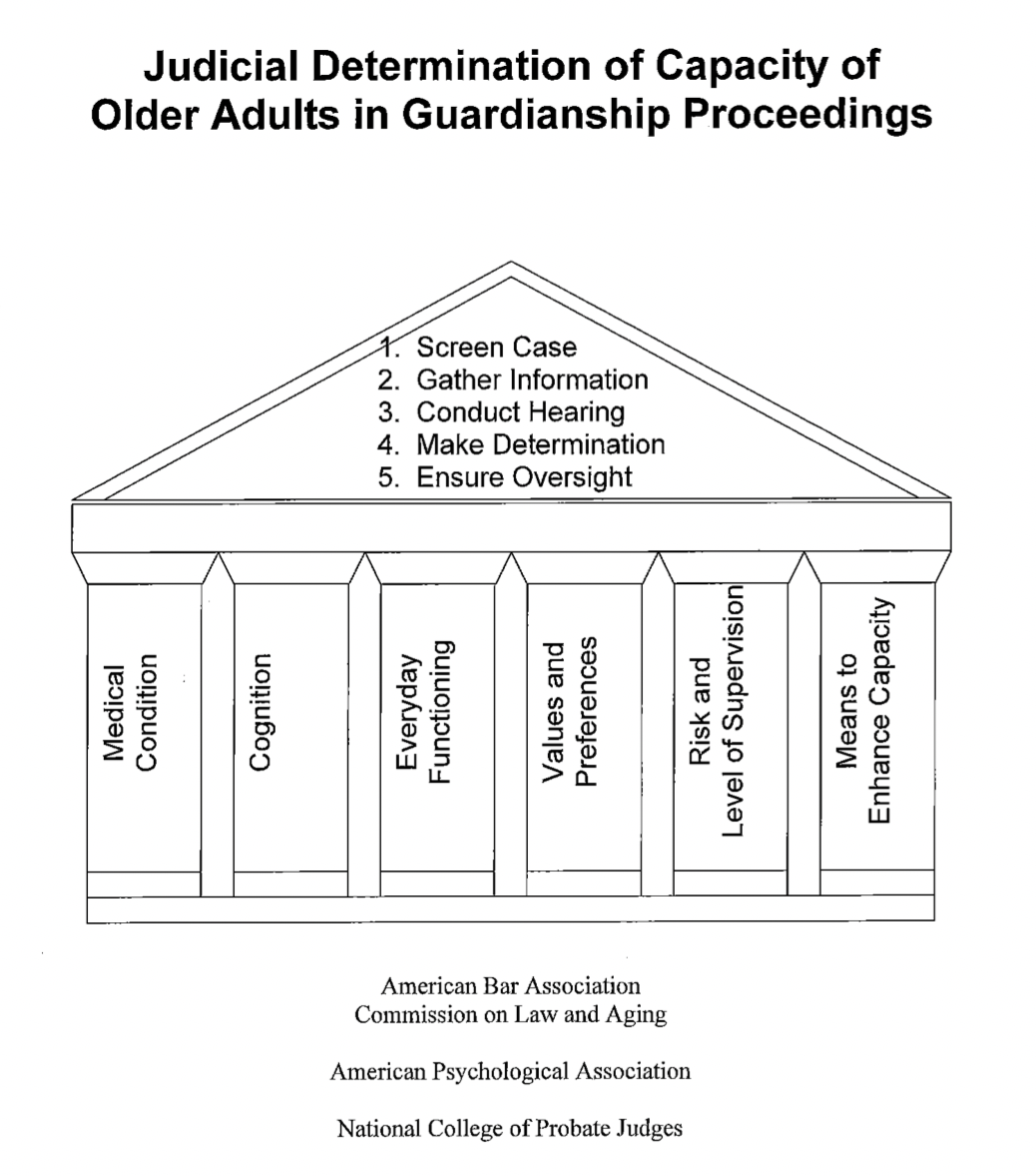

United States

When making a determination about capacity, all the below pillars of assessment must be considered and balanced.

More information About Capacity

Capacity Australia https://capacityaustralia.org.au/Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP): Test for medical capacity – What GPs need to know and Capacity to Consent to Treatment

MDA National: Assessment Of Capacity

Medical Journal of Australia; Purser and Rosenfeld: Evaluation of legal capacity by Doctors and Lawyers - Collaboration

Qld Law Society: Qld Handbook for Practitioners on Legal Capacity

Caxton Legal Service: Queensland Law Handbook

Legal Aid Qld Legal Capacity