Statutory Health Attorney

A statutory health attorney is someone with automatic authority to make health care decisions on a person’s behalf if the person is an adult whose capacity to make health care decisions is permanently or temporarily impaired.A statutory health attorney will make decisions about the person’s health care if they are too ill or incapable of making them. For example, consent may be needed for medical treatment or an operation while the person is unconscious. Or the person may have cognitive impairment and be currently unable to make their own decisions.

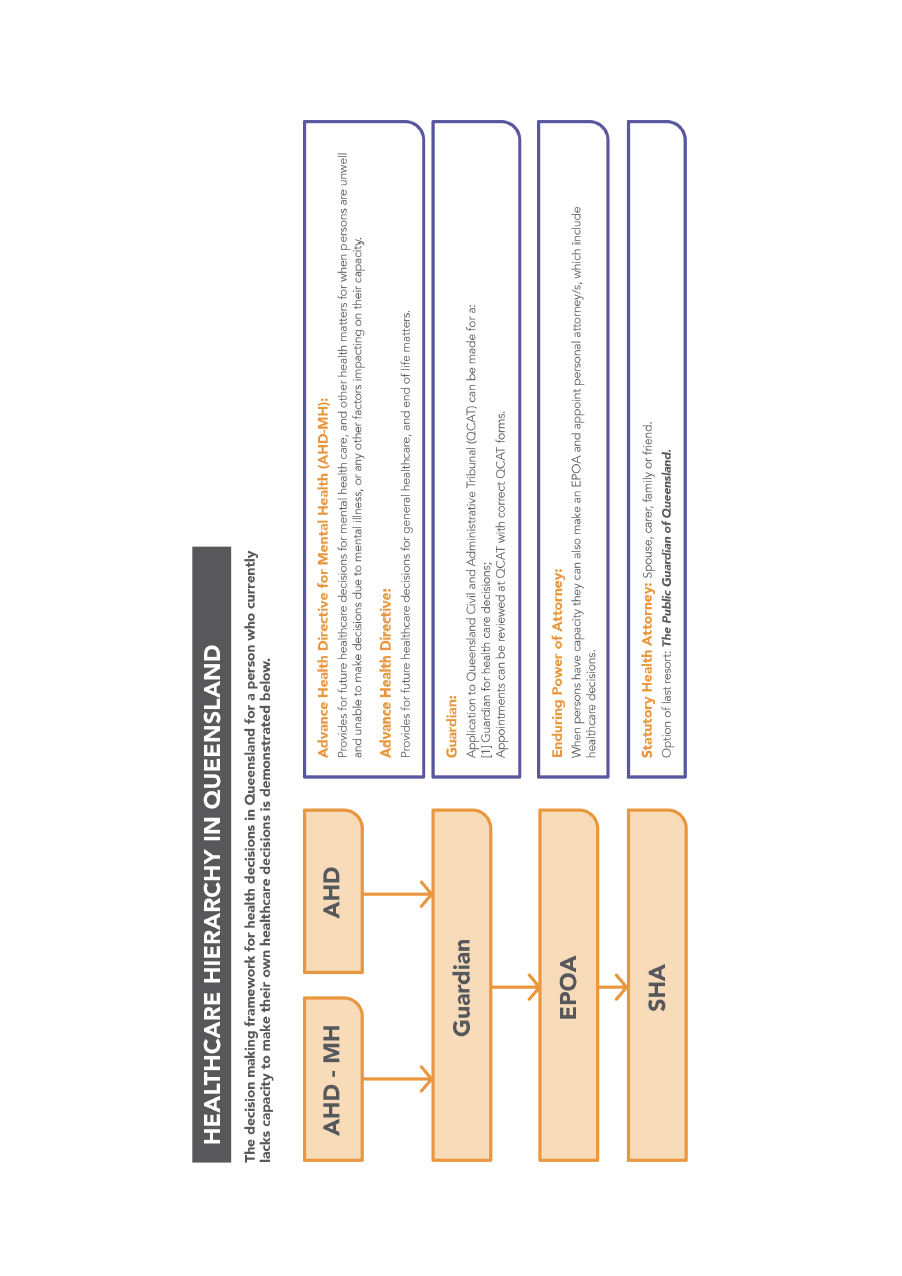

A statutory health attorney will act if the person has not:

- set out relevant directions for the person’s medical treatment in an advance health directive

- appointed an attorney for personal matters under an enduring power of attorney

- had a guardian appointed for health care matters by the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT).

A person acts in the role of statutory health attorney because of their relationship with the person. By law, it’s the first available and culturally appropriate adult from the following:

- a spouse or de facto partner (as long as the relationship is close and continuing)

- a person who is responsible for the adult’s primary care (but is not a paid carer, although they can receive a carer’s pension) or

- a close friend or relative (over the age of 18).

- If there is no one suitable or available, the Public Guardian acts as the statutory health attorney as a last resort.

Decisions a statutory health attorney can make

A statutory health attorney can consent to most health care decisions (for example medical and dental treatment), including withdrawing and withholding life-sustaining measures (for example CPR, assisted ventilation or artificial nutrition and hydration). They cannot consent to forensic examinations.Responsibilities of a statutory health attorney

Under the principles of Queensland law, all health decisions made for an adult must maintain or promote their health and well-being and be in their best interests.This means that when making any decision, a statutory health attorney must:

- choose the least intrusive treatment if options are available

- take the adult’s views, wishes and preferences into account as much as possible

- consider a doctor’s opinion.

Find out more about being a statutory health attorney in the Public Guardian fact sheet

Special health care matters for adults

There are some health decisions that a statutory health attorney cannot make. If someone doesn’t have an advanced health directive or an enduring power of attorney and is unable to make their own decisions, then the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT) must consent to the procedures.These are known as special health care matters and include:

- donation of tissue for a transplant (permission for organ transplants can’t be given while the adult is alive)

- sterilisation (vasectomy, tubal ligation or hysterectomy)

- abortion

- special medical research or experimental health care.

QCAT can then decide whether you’re appropriate to be an interested person.

Special medical procedures for Children

There are some decisions about special medical procedures that can’t be decided by a parent or guardian or the child, and must be decided by a court or Tribunal.These treatments are called special medical procedures and include:

- sterilising a child who has a significant intellectual disability

- organ donation when a child is unable to give informed consent

- medical practitioners recommending life-saving treatment but parents or guardians refusing to agree to the treatment (eg parents refusing for a child to be put on life support)

- parents or guardians disagreeing about significant, recommended treatment/s

- sensitive or ethically controversial issues (eg gender decisions for a child born with both genitalia)

- Refusing treatment in a life-threatening situation (eg child suffers anorexia nervosa and refuses treatment).

- a parent

- a person authorised by a parenting order

- a child

- an independent children’s lawyer

- anyone concerned with the care, welfare and development of a child.

Reference: Legal Aid